It’s what’s left when it’s gone,” Myles writes. “Light meets everything and it’s where the color goes. Rather, Myles and Rosie are shown to constitute each other through a myriad of mirroring games.īuilding from the theory of the ancient Greek philosopher Thales that we are all water, Afterglow shows that, more than just primordial ooze or bodily fluid, water can be toxic poison (alcohol) or a healing pool of light and lightness. The metamorphic, metempsychotic nature of the book evades genus but might be something like what Derrida called “zoo-autobiography,” which would not be a question of “‘giving speech back’ to animals but perhaps of acceding to thinking … the absence of the name and of the word … as something other than privation.” Rosie is never presented as a voiceless creature, a transitional object endowed with language by the author. While Rosie’s breed was Pit Bull, the book’s genre is a unique hybrid of its own. The visions that ensue seem to embody German Expressionist artist Franz Marc’s dictum that rather than paint animals in landscapes, we should paint landscapes seen through the eyes of animals.

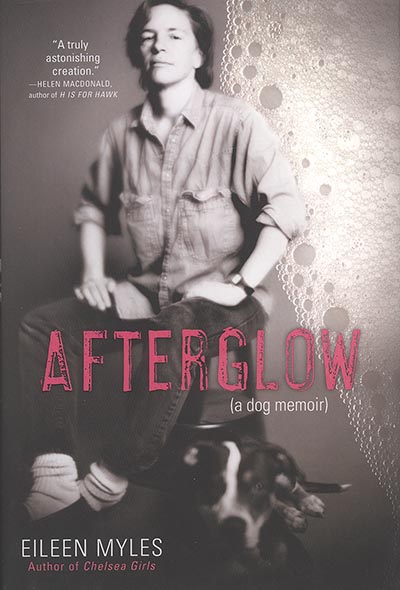

Myles’s assertive poetic voice is transfigured into Joycean landscapes that are seen through the eyes of Rosie and eventually synchronize with Myles. In Afterglow, contemplation extends past generic human boundaries. Together they recount their relationship through to Rosie’s death, while speculating on how memory is recollected and how it vanishes in reflection. Gertrude Stein famously wrote, “I am I because my little dog knows me.” The poet Eileen Myles has reshaped knowing into collaborative becoming in Afterglow, written in part from the perspective of Myles’s Pit Bull, Rosie. Eileen Myles and Rosie (photo courtesy of Eileen Myles)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)